At Home with carla bergman

A Note from the publisher

We're living in an unprecedented moment in history, and it's been amazing to see how people are pulling together to support one another. Here at TouchWood we've decided to ask our authors what has been keeping them busy during a time when we've all been asked to stay home to Flatten the Curve.Physical Distancing, Social Solidarity with carla bergman

All that you touch You Change. All that you Change, Changes you. The only lasting truth is Change. —Octavia Butler

During the past couple of weeks my life, like many others’, has become much busier. Because I work at home, my day-to-day life hasn’t shifted in drastic ways with social distancing, but I am busier now because we are in a global health emergency. And, like many, I am committed to creating and supporting webs of mutual aid and solidarity during COVID-19. This kind of organizing at a distance requires lots of phone calls, emails, Skypes, Zooms, etc., and it took some serious adaptation because prior to this my organizing and activism style had always been about bringing folks together, sharing food, and making sure we collaborated in person and then did whatever was needed. This situation we are facing is new terrain, requiring us to show up in new and unforeseen ways for and with each other. It’s been incredible to see folks adapt and be there for each other all over the world. The kinds of solidarity and mutual aid that has emerged is truly remarkable and awe inspiring (and is well documented, so I won’t go into detail here). For me, it is the light in these very dark times. And so, during this time, the biggest change for me was recognizing that COVID-19 was going to be long lasting—a marathon not a sprint—and that I needed to take breaks and pass on the mutual-aid baton. Pacing myself is key.

During the past couple of weeks my life, like many others’, has become much busier. Because I work at home, my day-to-day life hasn’t shifted in drastic ways with social distancing, but I am busier now because we are in a global health emergency. And, like many, I am committed to creating and supporting webs of mutual aid and solidarity during COVID-19. This kind of organizing at a distance requires lots of phone calls, emails, Skypes, Zooms, etc., and it took some serious adaptation because prior to this my organizing and activism style had always been about bringing folks together, sharing food, and making sure we collaborated in person and then did whatever was needed. This situation we are facing is new terrain, requiring us to show up in new and unforeseen ways for and with each other. It’s been incredible to see folks adapt and be there for each other all over the world. The kinds of solidarity and mutual aid that has emerged is truly remarkable and awe inspiring (and is well documented, so I won’t go into detail here). For me, it is the light in these very dark times. And so, during this time, the biggest change for me was recognizing that COVID-19 was going to be long lasting—a marathon not a sprint—and that I needed to take breaks and pass on the mutual-aid baton. Pacing myself is key.

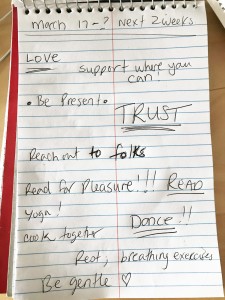

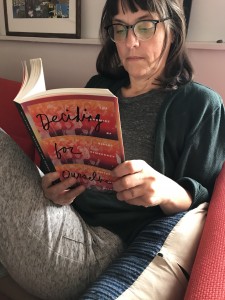

Personally, and maybe as a way to bring some levity into my day-to-day, I am always seeking out ways to find joy. Connected to finding joy, I also want to be able to do more, to increase my personal capacity, so I can do more for others. This requires some concrete daily practices: cooking, doing yoga (Yoga With Adriene is my go-to), resting when I can, and of course dancing! But to be honest, I also need a break from worry and being on call, and the only way I am truly getting a break is by reading. So I recommend getting some new books, and making time for reading. At the core, I aim to keep myself well, and that includes my mental wellness. As my friend Kitty Sipple so poignantly said, “I’m allowing this whole situation to light up areas inside myself that I’ve been avoiding.” Or, to put another way, I am sitting with the hard stuff that arises during these confusing and scary times. And, alongside this hard stuff, are many hopeful cracks that are providing infinite possibilities to emerge, ones that together we can imagine and enact a better world with, post COVID-19.

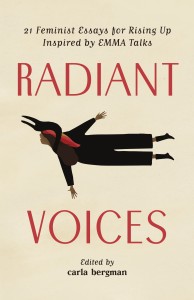

So, back to being home—where I think solidarity ought to begin—I want to offer an excerpt from the book I edited, Radiant Voices, because I am interested in reaching out to those who are lucky enough to be at home with kids during this time (and anytime). This is for anyone living in a space with young folks, whether they are your children, or a niece, or friend, doesn’t matter. If you are living with kids and youth, then I want to share this with you (the ideas in the essay work for any age group, though). I want to share this because our relationships are central to our thriving. There is no blueprint for how to do that well, but I do believe that solidarity takes root in listening to each other, and then responding to each other’s needs in the best way we can. We are all trying to process a global pandemic, and we all need some extra care and support.

I don’t know how to fix this, so I am just trying my best to feel it, and to be present with those in my home, my circle of friends, and to those in need. At the core, I aim to trust myself and the folks I love, and then respond and act from there. The future is always uncertain, so let’s stay present and listen to each other as we traverse these unknown and turbulent paths toward a better world for all.

Sending love and solidarity, carla

Personally, and maybe as a way to bring some levity into my day-to-day, I am always seeking out ways to find joy. Connected to finding joy, I also want to be able to do more, to increase my personal capacity, so I can do more for others. This requires some concrete daily practices: cooking, doing yoga (Yoga With Adriene is my go-to), resting when I can, and of course dancing! But to be honest, I also need a break from worry and being on call, and the only way I am truly getting a break is by reading. So I recommend getting some new books, and making time for reading. At the core, I aim to keep myself well, and that includes my mental wellness. As my friend Kitty Sipple so poignantly said, “I’m allowing this whole situation to light up areas inside myself that I’ve been avoiding.” Or, to put another way, I am sitting with the hard stuff that arises during these confusing and scary times. And, alongside this hard stuff, are many hopeful cracks that are providing infinite possibilities to emerge, ones that together we can imagine and enact a better world with, post COVID-19.

So, back to being home—where I think solidarity ought to begin—I want to offer an excerpt from the book I edited, Radiant Voices, because I am interested in reaching out to those who are lucky enough to be at home with kids during this time (and anytime). This is for anyone living in a space with young folks, whether they are your children, or a niece, or friend, doesn’t matter. If you are living with kids and youth, then I want to share this with you (the ideas in the essay work for any age group, though). I want to share this because our relationships are central to our thriving. There is no blueprint for how to do that well, but I do believe that solidarity takes root in listening to each other, and then responding to each other’s needs in the best way we can. We are all trying to process a global pandemic, and we all need some extra care and support.

I don’t know how to fix this, so I am just trying my best to feel it, and to be present with those in my home, my circle of friends, and to those in need. At the core, I aim to trust myself and the folks I love, and then respond and act from there. The future is always uncertain, so let’s stay present and listen to each other as we traverse these unknown and turbulent paths toward a better world for all.

Sending love and solidarity, carla

On the Last Leg of the Journey: An Interview with Helen Hughes

Excerpted: Radiant Voices

In thinking about Radiant Voices and voice generally—who has voice, who is listened to, and who is left out—I thought of Helen Hughes, my dear friend and one of my most important long-term mentors. To have a voice, you must have a listener. Helen is the person in my life who does this profound listening. She is always curious and open. Helen gave me voice, and I am forever grateful. She has given hundreds of others voice, too.

Helen co-created Windsor House, an alternative K-to-12 school in North Vancouver, back in the early seventies. For the past forty-eight years, she has been the matriarch of this democratically run school–community. The number of people who benefited from Helen is impossible to determine: it includes not just students, staff, and families directly involved at Windsor House, but also all who those folks encountered—the ripple effect is immense and truly awe-inspiring.

Here is my conversation with Helen about voice and listening.

Why and how did you get involved in education?

My parents were teachers, and my home life was secure. I spent my blissful teen years with my dog Topper in the wilds of Mosquito Creek in North Vancouver. I somehow blocked out my schooling—I was very good at seeming to pay attention while being somewhere else entirely. Adulthood came as a rude awakening. Just nineteen, I married, started teaching—forty-five students to a class in those days—and tried to learn how to shop, cook, and clean, as well as work full time. I came up short in all categories. That is when my education truly started.

The first thing I learned was to notice what people were actually saying. I learned a lot from my students. When my daughter balked strenuously at going to school in Grade 2, I got together with some other parents and started a school in my house. We knew what we didn’t want but had no clear picture of what we did want. The school wobbled along—with the fifteen children playing, making use of the many things available to them, while the parents talked endlessly about the philosophy of learning and teaching. We all read every book that came along. Summerhill was our role model. After four years, we could no longer manage privately, so we asked the North Vancouver School District to take us in, which they did. Alternative schools were all the rage in those days. Windsor House, so named because it started in a house on Windsor Road, grew and thrived. Eventually we had two hundred students, and I was made vice principal. My three children attended Windsor House, and now my grandchildren do as well. They are all fine people, so freedom can work if it suits your style.

Helen, you have always been part of educational projects and movements. Can you tell us some of the things you learned most from this work?

I thought, when I turned seventy-five, that I would just coast to the end. I’d lived a great life—felt joy, excruciating remorse, grief, a great deal of pleasure, and a lot of just managing from one day to the next. I worked hard and played hard, and now I could take it easy. How wrong I was! There is no rest for the curious, so I am careening down the last run of the rollercoaster—with my hair flying, my eyes wide open, and my ears perked. What I have learned most from this work is that listening to understand is completely different from listening to make a clever rebuttal.

What is next on the horizon for you?

I decided to spend what is possibly the last fifteen years of my life finding out who I am. I discovered, of course, that I keep changing, so I never really get a handle on it. Also, since I am so embedded in my culture, it’s hard to know what is the essence of me and what is the result of conditioning. I’m still curious about it but no longer see it as something I can actually complete. So now I’m hankering for one last project—something that I can manage, something simple, something where I won’t be letting people down as I become more doddering and forgetful.

I love that distinction of being part of culture—to know where you start and where the culture ends is challenging for any of us. Do you have any ideas on what that next project might be?

Well, what are my strengths? I don’t cook worth a damn, nor clean, nor garden, nor exercise, nor shop. Hmm. What I enjoy and what I do well is observe people and listen, in order to understand. As a result of this, I notice patterns. One of these patterns is that when people are in conflict and when they start to try to reason with each other, they often use reasons as weapons. They just keep coming up with reasons and counter reasons, and eventually the strongest, richest, loudest person wins, leaving the other person resentful. I rarely see someone say, “Oh, I see your point! Of course, you are right. Let’s do it your way.”

Reasons are so seductive, though. Check out this link, watch this video, read this quote—then surely, you will agree with me! This popular person, brilliant thinker, renowned scientist says this, so it must be true. It is very unusual to come across someone who is willing to set aside reasons in order to come to mutually agreeable solutions. I am of the opinion that there must be something better.

I agree—there has got to be a better way! I really like the idea of not using reason this way. Can you provide some examples?

My life’s work has made it possible for me to have many young friends, and I noticed that among the young people that I hang out with brainstorming seems more effective than sweet reason. The explanation for this is that it is hard for most humans to actually listen to another person’s reasoning because half of their brain is busy coming up with a rebuttal. If you are brainstorming, however—just throwing out ideas with no need to favour any particular one—then you can actually hear a suggestion that might appeal to you. Or you hear a suggestion that would work with a minor tweak. At that point, you are both on the same team, trying to create a solution that is good enough to try. Each suggestion should start with words like I have an idea, My suggestion is, How about we try, Could we. All suggestions are okay. If you don’t like one, then just ignore it. When you hear one you sort of like, then you can add to it with improvements.

For older folk, it is much the same: suggestions only, no negation of suggestions, no suggestions of reason or fairness, just possible ideas. The tentative solution need not be bulletproof; it just has to be worth trying. I have an example from today: My grandchildren arrived in a squabbling mood. I intervened. I said that if they were going to be on each other’s nerves I would put them in different rooms while I got lunch, and then we could do something together. They clearly didn’t want to be separated, so they both chimed in with good will. The eldest had built a fort in the living room and had used two giant padded boppers as door posts. He didn’t want his sister to play in his fort. The youngest suggested that they share the boppers. The eldest said no. I reminded them that the best brainstorming is without negation. If they don’t like a suggestion, just ignore it.

The next suggestion was for the eldest to carry on in his fort and the youngest to help with lunch—then, in quick succession:

-

- Hop around the house on one foot;

- Cooperate in the fort;

- Eldest play in the fort and youngest have candies;

- All make lunch together;

- Eldest get the living room and youngest eat grapes while I make lunch;

- Make lunch with feet tied together including me—I had a good laugh at this one, which raised the goodwill of the brainstorming;

- Eldest get the living room and the dining room and youngest get playroom and study;

- Play separately in the same room without bugging; make a fire in the fireplace and watch it.

Unfortunately, the word watch sounded a bit like wash, so the eldest said if we wash the fire, then it will go out. He was attempting humour, but it seemed like a put-down, so the energy dropped. I commended the joke and noted that the energy had dropped.

Then I suggested one outside and one inside. The energy was wobbling, and we were all hungry, so I resorted to a bulletproof idea that one could use my iPad and the other my iPhone. The eldest picked that up, but the youngest was, to my amazement, unmoved. I was getting hungry myself, so I went back to an old suggestion with a new twist. I suggested that we all make lunch together, but we could walk only on the green squares of the kitchen tiles. By then they were ready to settle. The suggestion by the youngest that the eldest run up and down the stairs while she counted was enthusiastically agreed upon. Go figure!

Why do you think it works?

I am puzzled by the apparent success of this rather odd method and wonder if it can be put to greater use. I recognize that some matters are actually life or death and that running up and down the stairs is not going to help. However, I do believe that in all disputes, things are either going to stay the same or they are going to change. Given that truism, it seems like a good idea to employ a style that is wide open and without judgments to at least find temporary solutions and at best make incremental changes to keep things from becoming too rigid to survive changing conditions.

This model gives voice and power to everyone involved. I think you have an incredible ability to remain curious and to trust both the people around you and the process. How did you learn these skills? Why is listening so important?

Back in the day when I was fostering young people, we had ample opportunity to try out some of these ideas. My favourite story was about one young person who always left the teapot dirty. When I went to use it, I had to wash it first. We tried this system then that system, but all of them failed. Finally, in a burst of brilliance, my boarder said, “Why don’t we both not wash the pot when we are finished with it. Then we only need to wash it just before we use it.” I was dumbfounded. My stance was so righteous and hers was so clearly wrong that it took a few moments while I processed the idea and realized it could work really well! Sure enough, when I washed the pot before I used it, the pot was warm as well as clean.

When I tell this story to a group of adults, they are often shocked. Some absolutely will not agree that it was a good solution. Somehow it offends a deep moral obligation to always clean up after yourself! This idea of right or fair gets in the way a lot.

What else gets in the way of people being able to approach decisions this way?

When I was at Hollyhock this summer, they had just issued a ruling that the hot tubs were no longer bathing suit optional. There was grumbling. I said to one gentleman, “Why don’t you ask if you can work out a solution with them?” “How could you do that?” he said, “Either you’re naked or you’re not—there is no compromise possible.” I was astonished. “There are many different options—have different hours for different dress codes; have one hot tub optional and the other bathing suits required; build a screen between the two pools; wear blindfolds; make a tent to put over one; have days on and days off; have times for different sexes, different ages, different moral codes; turn off all the lighting.” He was unmoved. I realize that my worldview includes casting about for unusual solutions for seemingly intractable problems. I don’t see things as either this or that. I see the world as a place of outrageously improbable solutions that astoundingly work.

Yes, I often say what about options three, four, five, and six? I am pretty sure I gained the ability to ask these questions from being around you. I like what you are saying here. It feels deeply relational, and it makes me think about collaboration. How does collaboration fit into this model?

Well, it’s an informal method of collaboration and can be done by almost anyone. When children have been supported to be successful using informal collaboration, they can do it easily and quickly by themselves in their day-to-day lives. More formal collaboration, however, can only be done by people of good will. It is only effective when meetings are run by a person who can hold everyone to an agreement. The agreement needs to be one of only coming up with ideas, with no spoken or physically indicated rejection. When the felt sense of the meeting moves the moderator to ask if all can agree to try a solution, there may be tweaking of the favourite suggestion to make it acceptable to all. Then comes raised hands to show agreement to support the solution for a given length of time. I notice that I have used the term only three times in one paragraph. I am wary of using absolutes, so I am open to revisiting this.

How do you see this in relation to the question of radical social change?

I remember being told that in any grouping—people, villages, algae—there had to be about eighty percent of the entities that stayed the same down through time and twenty percent that changed. This was to keep the organism from becoming too rigid to accommodate changing conditions or from becoming too flexible to hold together. This idea made me much more appreciative of all of the rigid systems that hinder the implementation of my wild fancies. Nonetheless, I am very grateful for those folks who get out there and insist on change. You are the ones who get squished and maligned, but you are the ones who will save the day.

If you had one piece of advice to give to those of us who want to see social change in the world, what would it be?

My advice would be to support one another. If the group you are in heads in a direction you don’t want to go, leave. Find a more compatible group or start one of your own. Do not put sand in the gears of a machine that is working. In my lifetime, I have seen many worthwhile groups implode while fighting with one another over insignificant details. Oddly enough, this seems to be a more left-wing issue than a right-wing one. The Right seems more capable of coming up with simplistic ideologies that tap into visceral support, while the Left seems to want to fine-tune to perfection before going into action.

When you find a group that you like, appreciate the work of others in your group, use goodwill to understand different ideas, turn criticisms into suggestions, and don’t break into secret groups. If you think someone should do something differently, then model how effective your method is. Move toward the trouble—it rarely goes away on its own. Talk with the person you understand the least and listen closely so that you can explain their position with grace. I want to be clear that I do not oppose militancy. There are some groups that need to be stopped. The KKK comes to mind. I’ll leave it to you young people to find ingenious ways to fight intolerance and greed

If you have a copy of Radiant Voices, or are able to get one during social-isolation, there are few more essays that stand out as being particularly helpful for this time:- We Owe Each Other Kindness by Kinnie Starr*

- Spirit. Magic. Revolution. by Shaunga Tagore

- Everything Inside of Us, by Tasnim Nathoo

- *All the Ways that Capitalism Sucks (or at Least Some of Them), by Kian Cham*

- *Two Stories, by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson

- *Where are the Gears? Thoughts on Resisting the (Neoliberal, Networked) Machine, by Astra Taylor